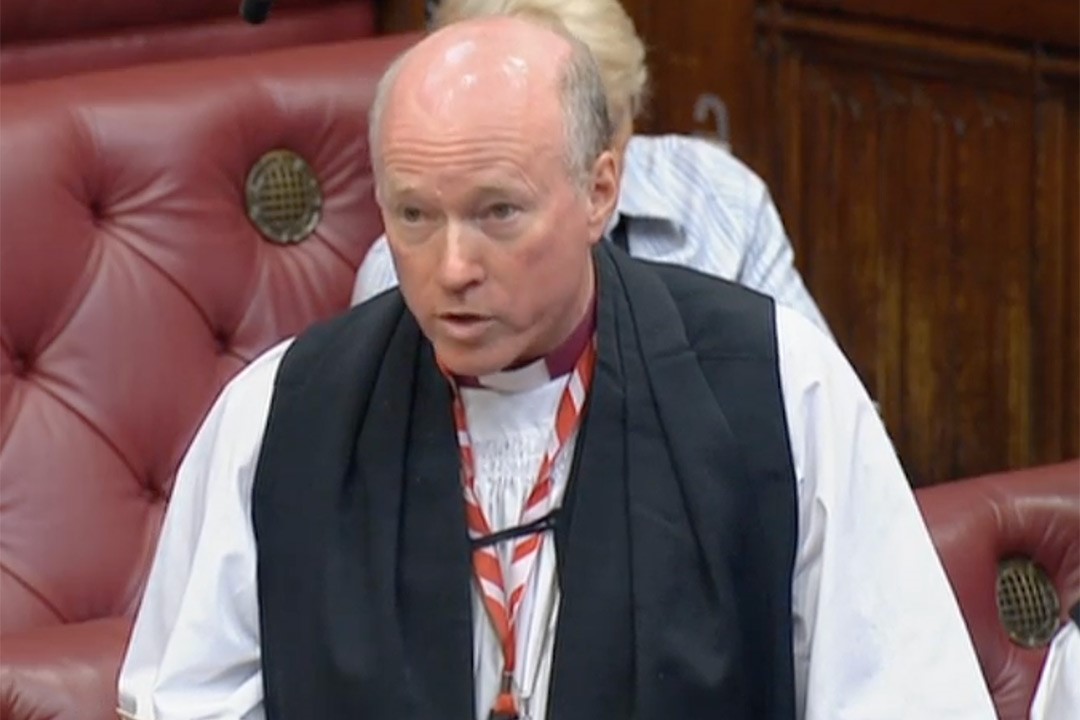

Maiden Speech by the Bishop of Southwell & Nottingham – 21 July 2022

On the impact of the Russian blockade of Ukrainian ports on food insecurity in developing countries, and its contribution to the danger of famine in (a) the Horn of Africa, and (b) East Africa. You can watch the speech here.

My Lords, may I begin first by thanking fellow members for their gracious welcome, as well as expressing my gratitude to parliamentary staff and officers who have so kindly supported my introduction to the House.

It is an honour to make this maiden speech in such an important debate. Focussing so clearly on the needs of the most vulnerable affected by the sudden and steep rise in global food prices, resulting from Russia’s terrible war in Ukraine. I want to pay tribute to the noble Lord, Lord Alton for bringing this debate to the House and for his long record of campaigning advocacy on behalf of those whose suffering is too often overlooked.

It is more than 12 years since a Bishop of Southwell and Nottingham has been in this House, though the previous bishop has been a passionate advocate for the poor and young since joining the House as my noble friend, the right reverend prelate, the Lord Bishop of Durham.

Nurturing the aspirations and potential of young people, particularly in their influence and impact as future leaders, has long been a distinct feature of my own work. First for 17 years in parish ministry, including ten as a vicar in South Buckinghamshire; then for 13 years as bishop, starting out in West London as area Bishop of Kensington and now for the past 7 as a Diocesan Bishop in the East Midlands here along with my family, I have come to feel very much at home. It is interest in the development of young people that underpins my contribution to the debate today.

While the city and county of Nottingham is perhaps most famous for the folklore hero Robin Hood, the region has a long track record for nurturing many lesser known heroes who have nonetheless been world shapers, championing the cause of the poor and the young; including the inspirational founders of the Salvation Army, William and Catherine Booth. Since moving to the diocese, I have been inspired by modern heroes on the ground making a difference to the life chances and prospects of young people, proving that nurturing every talent matters.

Yet what has struck me most is that although parts of the city and county continue to struggle with higher than average levels of poverty, the aspirations of young people are rising and their innate instinct to make a difference is far from parochial. Their outlook is global. They see themselves as part of an interconnected and increasingly interdependent world. That is why there should be no tension between charity at home and abroad. Their example inspires my engagement in this debate today.

Compassion for those who suffer was characteristic of Jesus Christ, and in the Gospels it is clear that he frequently surprised those around him by disturbing their inclination to limit the boundaries of who may qualify as a neighbour and how far their responsibility to care should extend. The lessons of the Good Samaritan are rightly deeply imbedded into our spiritual heritage as a nation. I suggest it should inform our urgent response to the crisis in the Horn of Africa and East Africa. This is no time to look away.

[According to the United Nations Office for Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) there are now 7.1m children malnourished in the Horn of Africa and 2m severely malnourished. The position is similar in East Africa]. I want to draw particular attention to how the needs of young people are disproportionately affected by food insecurity, not only on their health but also their education and life chances.

Informed by some valuable links that churches in my Diocese have with schools in Uganda, it is clear that the food crisis is already causing many schools to reduce their teaching week as they simply don’t have enough food for the children in their care.

According to the World Food Programme one in three school children in Uganda have no food to eat during the school day. Feeding learners has become an essential priority for schools.

Families in desperate need also keep children out of school. Instead they work to help earn a little more to pay for the cost of food that has risen by nearly 14% since January. This in a country that has the highest number of refugees and asylum seekers in Africa: as of March, nearly 1.6m. With acute malnutrition rising fast among under 5’s, many thousands will not even reach school age.

This is not only a short-term crisis of survival. It has longer term tragic consequences, undermining the capacity of a rising generation to be equipped with the education, skills and personal support they need and deserve. [There are tens of thousands of teachers in Uganda, and no doubt elsewhere in the region, who have a heart-felt and compelling vision for their students. They see the difference that a consistent, supportive and uninterrupted education can make to the future of the nation. This can also be a major contributor to food system resilience in the longer term, which must be an important goal]

It is true that large sums have already been given, both bilaterally and through multilateral projects in these regions, but the need is now greater still and we should not wait until a famine is declared.

While thankful for any signs of progress that may result in the recent initiative by the Turkish Government to provide safe passage for grain from Ukraine, I would ask the Minister that the government consider increasing further bilateral aid to the Horn of Africa and East Africa without delay. It is not too late to save lives and perhaps yet prevent a devastating famine with the unacceptable human cost that will result. And in the longer term, immediate intervention will improve the prospect and God-given potential of millions of young people in the region.